|

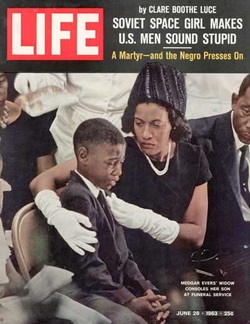

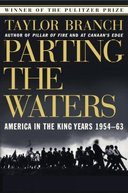

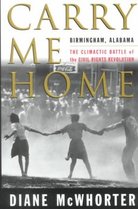

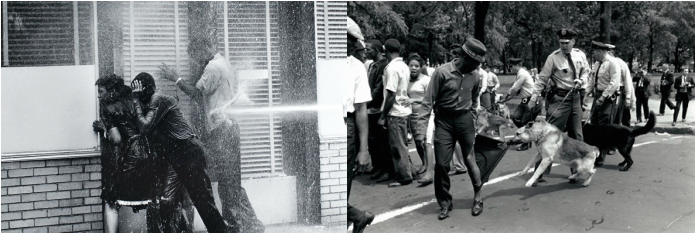

While everyone else seems obsessed with looking back at the best and worst of 2012 (of which there was, I admit, a lot), I suggest we make like Mr. Peabody and set the WABAC Machine to 1963 and take a stroll through all the good, bad and ugly events that will be celebrating their 50th anniversaries in the coming year. Ready, Sherman?  "Set the controls to 1963." We set the WABAC controls for the territory of the American South and just like that we are at Ground Zero of the Civil Rights Movement. 1963 is a year of pivotal moments in the quest for human rights in the United States, some triumphant and some tragic.  Gantt outside Clemson University In January, African-American student Harvey Gantt enrolls in Clemson University in South Carolina, which is the last state to hold out again racial integration. In the spring, Birmingham, Alabama becomes the epicenter of demonstrations. On April 16, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested and jailed there during anti-segregation protests. During his confinement, he writes his seminal "Letter from Birmingham Jail," in which he argues that individuals have a moral duty to disobey unjust laws. The following month, Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene "Bull" Connor turns his fire hoses and police dogs on black demonstrators. The images of police brutality are televised and published widely, increasing sympathy for the movement throughout the country and across the globe.  LIFE cover of Evers' funeral The movement suffers a harsh blow with the assassination of Medgar Evers, an activist and field secretary for the NAACP, outside his Mississippi on June 12. At summer’s end, African-American sociologist, historian and civil rights activist, W.E.B. DuBois dies. The very next day, August 28th, the March on Washington takes place and 200,000 participants gather for peaceful protest and to hear King deliver his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Monument. Just 18 days later, a bomb explodes at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four young girls attending Sunday school. The church is frequently used for movement meetings. Riots erupt, leading to the deaths of two more black youths.  Malcolm X In the waning of the year, on November 13, Malcolm X gives a speech in Detroit, Michigan commonly known as the “Message to the grassroots.” In the address, given before the Northern Negro Grassroots Leadership conference, he makes a seminal statement on Black Power and the Civil Rights Movement, defining revolution and arguing in favor of a worldwide union of nonwhites against the powerful and privileged who benefit from white racism. So there you have it. In 1963, the small sparks of freedom kindled by activists through voter-registration drives, lunch counter sit-ins, and Freedom Rides ignite into a fire which consumes the entire South. Just 50 short years ago... To read more about it...  Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1958-63 Taylor Branch (Simon and Schuster, 1988) First book of a trilogy, this Pulitzer Prize winner focuses on Martin Luther King, Jr., and the key moments that defined his rise to the forefront of the civil rights movement in America, from Rosa Parks' arrest in Montgomery to King's imprisonment in Birmingham and his triumphant march on Washington.  Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama Diane McWhorter (Simon and Schuster, 2001) A journalist who grew up in Birmingham as a member of one of the city's leading families chronicles the peak of the civil rights movement, focusing on the African-American freedom fighters who stood firm on issues of civil rights and segregation during the movement's eventful climax.  On the Road to Freedom: a guided tour of the civil rights trail Charles E. Cobb, Jr. (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2008) An award-winning black journalist takes a pilgrimage through the sites and landmarks of the civil rights movement as he journeys to key locales that served as a backdrop to important events of the 1960s, traveling around the country to pay tribute to the people, organizations, and events that transformed America. Stayed tuned for our next episode, in which the WABAC Machine will help us pinpoint some of the lighter events and inventions which will celebrate their golden anniversaries in 2013...

0 Comments

The first Monday in September, Labor Day, is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers, including the quantities of blood, sweat and tears they have shed in their contributions to the strength, prosperity, and Gross National Product of the United States. (As a person who once spent a summer as a card-carrying member of the United Steelworkers' Union, I can testify to the amount of sweat shed.) Depending on what you read, this holiday for workers was the brainchild of either Peter J. McGuire, a cofounder of the American Federation of Labor, or Matthew Maguire, a machinist and later the secretary of Local 344 of the International Association of Machinists. (I can see how they might be confused!) The first Labor Day holiday was celebrated on Tuesday, September 5, 1882, in New York City, sponsored by its Central Labor Union. In 1884 the first Monday in September was selected as the holiday, and the Central Labor Union urged labor organizations in other cities to follow their example and celebrate a "workingmen's holiday." The idea spread with the growth of the labor movement, and in 1885, Labor Day was celebrated in many cities with strong industrial bases across the country. On June 28, 1894, Congress passed an act making the first Monday in September of each year a legal holiday in the District of Columbia and the territories. Lately labor unions have been under attack by various factions in the U.S. political galaxy so it might be time to take a moment or two to read more about the history of labor in this country in order to fully appreciate the journey and the struggle of our predecessors. What better way to do that but with a well-written piece of nonfiction?!?  There is Power in a Union Philip Dray (Doubleday, 2010) From Lowell to Ludlow, from Haymarket Square to the ill-fated 1981 PATCO strike, the history of the labor movement has indeed been an epic journey and Dray captures it all in a crisp narrative that highlights vivid characters and dramatic scenes. Heroes, scoundrels, shining moments and scandals, the story of labor is the story of America, and it brought to life in the hands of a fine writer, who presents an even-handed account, although it is clear where his sympathies lie.  The Battle of Blair Mountain Robert Shogan (Westview Press, 2004) The violent nationwide Great Railroad Strike of 1877 may have involved more workers, but the Battle of Blair Mountain, WV, in August 1921 was the largest armed labor uprising in the United States. Nearly 10,000 white and black coal miners of the United Mine Workers of America attacked 3000 pro-coal company men. Here is a riveting tale of dissent, human rights, ancient enmities (a Hatfield of that infamous family is in the mix), and the threat of federal troops attacking citizens.  The Man Who Never Died William M. Adler (Bloomsbury, 2011) Inspiration to songwriters from Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger to Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, Joe Hill was a labor activist who became a legend. In 1915, Hill was executed in Utah for a murder it remains doubtful he committed. A proud member of the Industrial Workers of the World (colloquially known as "the Wobblies"), the most radical union of the early 20th Century, Hill was known for his humorous yet aggressive protest songs. Set to popular tunes and featured in the IWW's Little Red Songbook, they were pointed attacks on the establishment. Hill's famous "The Preacher and the Slave" mocks the hypocrisy of offering spiritual advice before worldly sustenance and introduced into the American lexicon the phrase "pie in the sky." Adler has scoured newspapers, archival sources, and related significant biographies to bring Hill's story to life and to deliver the man behind the myth. Today I want to sing the praises of authors who focus on nonfiction -- but who are able to turn facts into gripping drama that keeps you turning the pages long after you should have turned off the light.

I am currently reading Hot, Flat and Crowded by Thomas Friedman (Version 2.0) and I can barely tear myself away from the book. Okay, the topic is already compelling: our global environmental crisis. (And if you've spent any time in the Midwest and southern Great Plains this summer, you would be witness to evidence that global warming is not a myth: severe drought in many southern areas, extended heat waves, and extremely violent storms and flooding in the north.) So, yes, he's already got me at the topic -- but his way with the written word is compelling as well. His sentences are vivid; his choices of anecdotes and quotes are incisive; and his ability to take a dense concept and slice it into accessible, digestible chunks should be the envy of all writers. And, above all, he writes with passion about his topic. That's something that we teachers tell our students all the time: choose a topic that you are passionate about and your writing will benefit immensely. It's something that I notice in my book club discussions: the best discussions grow out of books that we either loved or hated. The mushy middle provokes nothing but more mush. Jon Krakauer, author of Into the Wild and Into Thin Air, is another writer who breathes both poetry and the tension of the commercial cliffhanger into nonfiction. "Nonfiction that reads like fiction" may be a cliche, but I was there on Mount Everest with the climbers. Krakauer's descriptions of the disastrous 1996 expedition had me checking my own fingers and toes for frostbite; kept me up until 3 a.m. compulsively reading "just one more page" because I couldn't bear the thought of leaving those foolhardy, yet brave men and women clinging to life on the mountain. I recently re-read The Devil in the White City for my book club and once again fell under the spell of Erik Larson's incredible nonfiction writing. As a Chicago girl, born and bred, I appreciated the extent to which he delved into his topics: the creation of the 1893 World's Fair juxtaposed with the serial killer H.H. Holmes. His details are meticulous -- his prose is compelling, even nail-biting as he swoops from the the broad expanses of the fairgrounds as the exhibition is slowly, agonizing shaped by the hand of architect Daniel Burnham to the claustrophobic confines of the hotel of death that Holmes built and to which he lured his fair-going victims. This is nonfiction writing that sinks it teeth in you and doesn't let go. |

AuthorTo find out more about me, click on the Not Your Average Jo tab. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed