|

No, I'm not talking about the Duchess of Cambridge (although I am sure she's a very fine person, charming and all that, but my fascination with British royalty died with Diana...) No, I'm referring to birthday girl Kate DiCamillo, Newbery-Award winning author of some of my favorite children's books.  Kate DiCamilllo (courtesy NPR) As a child, Kate moved from Philadelphia to a small town in Florida. As she writes in her Scholastic website bio: "I was a very sickly kid, and suffered from chronic pneumonia, which is why we moved to the warm southern climate. I think being ill contributed to my development as a writer. I learned early on to entertain myself by reading. I learned to rely on stories as a way of understanding the world. I read everything I could, and some of my favorites were The Twenty-One Balloons, The Secret Garden, The Yearling, Ribsy, and a book called Somebody Else's Shoes." Her first book, Because of Winn-Dixie, came out of that Southern experience and childhood memories of a beloved pet and was partly the result of being homesick and dogsick (she was living in Minneapolis at the time and was unable to have a dog in her apartment). As she notes, writing that story "allowed me to go home and to spend time with a dog of the highest order." So here's a Read More About It birthday salute to Kate:  Mercy Watson: to the Rescue Whether or not you're a fan of pork, you won't be able to resist this porcine parcel of personality and pluck. In this first of six adventures, Mercy's single-minded pursuit of her culinary favorite, hot buttered toast, leads to a series of comic semi-disasters. But all ends well, warm and buttery. Other titles in the series of beginning chapter books include: Mercy Watson Goes for a Ride, ...Fights Crime, ...Something Wonky This Way Comes, ...Thinks Like a Pig, and ...Princess in Disguise. The illustrations by Chris Van Dusen add to the hilarity and charm.  Louise: The Adventures of a Chicken Who doesn't long for a little adventure in his or her life? Well, Louise is no different from the rest of us -- except, of course, that she's a chicken. Literally. Not just any chicken, but a daring chicken who sets out on her quest with spirit and spunk. As she sees the world, she also manages to: escape from a band of pirates, perform in a daring circus act, and get trapped in a cage by a stranger. When she finally arrives home to tell her fellow hens about her ordeals, she realizes, like another farm-girl before her, that "there's no place like home." An exceptionally funny and entertaining read aloud, with fabulous illustrations to accompany and elaborate on the text.  The Tale of Despereaux Impossible wishes and longings fill this story: a mouse yearns for joys of reading and the love of a princess; a rat burns to leave the darkness of his home in the dungeons of a castle; a slow-witted servant girl dreams of becoming the highest lady in the land. Despereaux, the mouse-hero, is one of many in the castle, but he is different. He was born with his eyes open (weird!), his ears are too big (shocking!) and he likes to read (that's just wrong!). Worst of all, he has fallen in love with the very human Princess Pea and has even dared to speak to her. This gets him banished to the dark, dark dungeon where the evil rats dwell, which in turn sets in motion a chain of events involving the rat and the servant that will require Despereaux to be as brave as the knights he has read so much about in order to save the lovely princess. If you like a bit of darkness (or more) in your children's books, this Newbery winner will definitely satisfy. So happy birthday, Kate, and onto the next story!

0 Comments

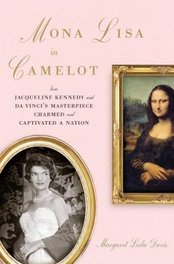

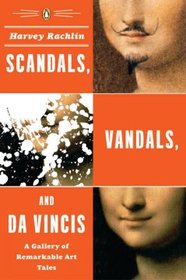

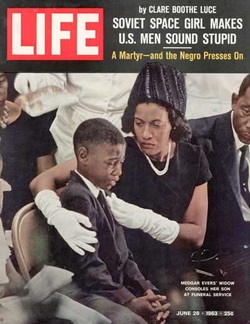

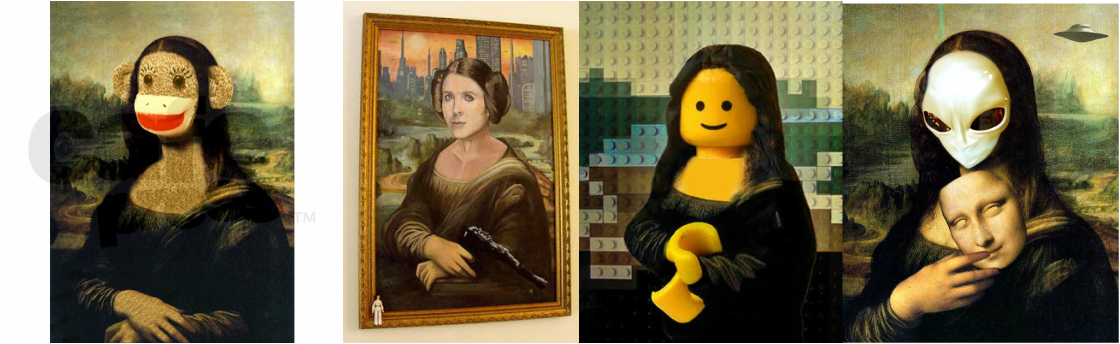

The unveiling: LBJ is particularly entranced January 13th marks the 50th anniversary of Mona Lisa's famous debut in the United States. Her unveiling at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. was reminiscent of a coronation, presided over by triumphant First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy, who had been instrumental in negotiations with the French government to send the priceless painting on its first overseas trip. Using her considerable powers of persuasion (and her knack for speaking French), she convinced France's Minister of Culture, Andre Malraux, that an artistic exchange of this magnitude would strengthen the cultural ties between the nations. French President Charles de Gaulle, who was looking to cement his stature on the international political scene during the cold-war years, saw it from a different perspective. He wanted to develop a nuclear arsenal and needed the tacit support of the American government to do it. If the mysterious, come-hither smile of a 450 year old woman could seal the deal, well, son sac dans le coffre et l'envoyer sur l'océan. To read more about the adventures of the first lady of art, you don't have to cross the seas. Just venture to your local library for these entertaining reads:  Mona Lisa in Camelot Davis, Margaret L. (Da Capo Press, 2008) The author details the story of the 1963 American exhibition of the Mona Lisa in New York City and Washington, D.C. It was America's first blockbuster art show and the populace was gripped by "Mona mania." It's all here: the negotiations, preparations, flummoxes (the painting wound up being poorly lit in D.C.) and successes of the exhibit, along with plenty of inside dope on Jackie's phenomenal wardrobe.  Vanished Smile: the mysterious theft of the Mona Lisa Scotti, R. A. (Knopf, 2009) This is a spritely account of the brazen 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre and the two-year quest to bring her home. On the morning of August 22, La Joconde was found missing from the Salon Carré. Even with help of renowned French criminologist Alphonse Bertillon, the trail was cold from the start. Rumors abounded about greedy, wealthy American collectors and the Louvre’s lax security. No one in Paris was above suspicion, not even the young Pablo Picasso. While the portrait was finally recovered in Florence in 1913, its theft apparently the result of a young Italian’s misguided patriotism, the author reminds readers that the mystery is far from over. The true motive for the theft—and the possible connection to a larger ring of art thieves—remains unknown.  Scandals, vandals and DaVincis: a gallery of remarkable art tales Rachlin, Harvey (Penguin, 2007) For a mix of art gossip and intrigue, here's light-hearted but occasionally riveting account of the backstories of 26 famous paintings, beginning with the Mona Lisa. The author takes a close-up look at the secret histories of these masterpieces, including Gilbert Stuart's Athenaeum Head of George Washington, the world's most reproduced image (on the $1 bill). He describes how they came to be created and how they survived forgery, revolution, burglary, vandalism, ransoms, scandal, religious turmoil, and shipwrecks to become to some of the world's most priceless works of art. While everyone else seems obsessed with looking back at the best and worst of 2012 (of which there was, I admit, a lot), I suggest we make like Mr. Peabody and set the WABAC Machine to 1963 and take a stroll through all the good, bad and ugly events that will be celebrating their 50th anniversaries in the coming year. Ready, Sherman?  "Set the controls to 1963." We set the WABAC controls for the territory of the American South and just like that we are at Ground Zero of the Civil Rights Movement. 1963 is a year of pivotal moments in the quest for human rights in the United States, some triumphant and some tragic.  Gantt outside Clemson University In January, African-American student Harvey Gantt enrolls in Clemson University in South Carolina, which is the last state to hold out again racial integration. In the spring, Birmingham, Alabama becomes the epicenter of demonstrations. On April 16, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is arrested and jailed there during anti-segregation protests. During his confinement, he writes his seminal "Letter from Birmingham Jail," in which he argues that individuals have a moral duty to disobey unjust laws. The following month, Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety Eugene "Bull" Connor turns his fire hoses and police dogs on black demonstrators. The images of police brutality are televised and published widely, increasing sympathy for the movement throughout the country and across the globe.  LIFE cover of Evers' funeral The movement suffers a harsh blow with the assassination of Medgar Evers, an activist and field secretary for the NAACP, outside his Mississippi on June 12. At summer’s end, African-American sociologist, historian and civil rights activist, W.E.B. DuBois dies. The very next day, August 28th, the March on Washington takes place and 200,000 participants gather for peaceful protest and to hear King deliver his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Monument. Just 18 days later, a bomb explodes at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, killing four young girls attending Sunday school. The church is frequently used for movement meetings. Riots erupt, leading to the deaths of two more black youths.  Malcolm X In the waning of the year, on November 13, Malcolm X gives a speech in Detroit, Michigan commonly known as the “Message to the grassroots.” In the address, given before the Northern Negro Grassroots Leadership conference, he makes a seminal statement on Black Power and the Civil Rights Movement, defining revolution and arguing in favor of a worldwide union of nonwhites against the powerful and privileged who benefit from white racism. So there you have it. In 1963, the small sparks of freedom kindled by activists through voter-registration drives, lunch counter sit-ins, and Freedom Rides ignite into a fire which consumes the entire South. Just 50 short years ago... To read more about it...  Parting the Waters: America in the King Years, 1958-63 Taylor Branch (Simon and Schuster, 1988) First book of a trilogy, this Pulitzer Prize winner focuses on Martin Luther King, Jr., and the key moments that defined his rise to the forefront of the civil rights movement in America, from Rosa Parks' arrest in Montgomery to King's imprisonment in Birmingham and his triumphant march on Washington.  Carry Me Home: Birmingham, Alabama Diane McWhorter (Simon and Schuster, 2001) A journalist who grew up in Birmingham as a member of one of the city's leading families chronicles the peak of the civil rights movement, focusing on the African-American freedom fighters who stood firm on issues of civil rights and segregation during the movement's eventful climax.  On the Road to Freedom: a guided tour of the civil rights trail Charles E. Cobb, Jr. (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2008) An award-winning black journalist takes a pilgrimage through the sites and landmarks of the civil rights movement as he journeys to key locales that served as a backdrop to important events of the 1960s, traveling around the country to pay tribute to the people, organizations, and events that transformed America. Stayed tuned for our next episode, in which the WABAC Machine will help us pinpoint some of the lighter events and inventions which will celebrate their golden anniversaries in 2013...

Maybe you're like poor little Abby... Or maybe you're not...in which case, if you'd like to continue to get your political freak on after this election is over in 3 days (on the other hand, is the campaign ever really over???), but I digress... If you believe that the race for president used to be a kinder, gentler process... have I got some books for you!  Let's start with an intriguing read about the very first presidential campaign... A Magnificent Catastrophe: the tumultuous election of 1800, America's first presidential campaign Edward Larsen (Free Press, 2007) Here's a vivid retelling of the presidential election campaign between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson that brings the fierce rivalry that was called "America's Second Revolution" to brawny, brawling life and reveals the pivotal roles played by Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr. The bitter infighting and the sophisticated political jockeying of 1800 put paid to the notion that America would be governed by enlightened consensus. Instead, it resulted in the two-party system we know today. Readers will find a plethoria of similarities between the intense electioneering of THEN, and the heated political races of NOW. (Same as it ever was...)  Leaping ahead almost 100 years... Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan, and the Remarkable Election of 1896 R. Hal Williams (University of Kansas Press, 2010) The presidential election of 1896 is widely regarded as one of the few that brought about fundamental changes and realignments in American politics. New voting patterns emerged, a new majority party seized power, and national policies underwent a paradigm shift to reflect new realities. The monumental struggle between Republican William McKinley and Democrat William Jennings Bryan set new standards in financing, organization, and accountability. Back then, the Republicans were the party of central government, national authority, sound money (think: the gold standard), and activism, while the Democrats preached state's rights, decentralization, inflation, and limited government (and the silver standard). (Say what????!!! I know, you have to read it to believe it!) It's also the campaign that birthed Bryan's stem-winder "Cross of Gold" speech. Williams paints a vivid portrait of down-and-dirty, two-fisted politics when the participants still wore waistcoats.  On the lighter side.... A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the White House: humor, blunders, and other oddities from the presidential campaign trail Charles Osgood (Hyperion, 2008) You can always count on Charles Osgood to provide a good laugh while he enlightens. Here he presents a treasury of anecdotes from presidential campaigns over the past seventy years. You'll find lighthearted speech excerpts, interviews, and press-conference quotes from the campaigns of such presidents as FDR, Truman, and JFK. Who could imagine the dour Bob Dole wise-cracking to reporters? But after a loss in the primary, he quipped: "I slept like a baby--every two hours I woke up and cried."  Campaign coverage... gonzo style: Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72 Hunter S. Thompson (Warner Books, 2006) Darkly humorous, off-beat, moody... to say the least. In this newer edition of the classic account of the dark, very dark, underbelly of American politics, the original "gonzo" political journalist presents his frankly subjective, very subjective, observations on the personalities and political machinations of the 1972 presidential campaign between Richard "Tricky Dick" Nixon and the straight-arrow George McGovern, who just passed away at the age of 90 on a few weeks ago.  Pair it with... The Selling of the President Joe McGinniss (Penguin, 1988) McGinnis wormed his way into the inner sanctum of Richard Nixon's 1968 campaign for president. What he found was a nest of advertising technicians, ghost writers, P. R. experts, and pollsters who cynically plotted the re-branding of a loser into a winner and the clever packaging that sold America the most corrupt Presidency in its history.  You ever wonder what type of person actually thinks he (or she) is qualified to be President of the United States? Crack this one open... What It Takes: the way to the White House Richard Ben Cramer (Random House, 1992) Talk about the audacity of hope? How do these people convince themselves that they have the right stuff to sit behind a desk in the Oval Office and trod the floor where Lincoln, Roosevelt, Truman and Eisenhower paced? (Okay, Roosevelt didn't pace, he wheeled.) Journalist Cramer chronicled the 1988 campaign and put the candidates -- Robert Dole, George H.W. Bush, Joseph Biden, Richard Gephardt, Gary Hart and Michael Dukakis -- under the microscope and on the analyst's couch to glean some insight into the qualities that lead to success or failure as a presidential candidate. Watch the candidates as they make their way through the primaries, fine-tuning stands on issues, struggling to retain their individuality while being hounded by ravenous journalists, pummeled and massaged by numerous handlers and browbeaten by their image wizards. Dukakis comes off as a humorless know-it-all (maybe it's a good thing he lost), while Bush the Elder emerges as a compulsive nice guy and witty, too, such as when he quips, "I deny that I have ever given my opinion to anybody about anything.'' The ability to read + the ability to vote (and actually doing so) = Freedom.

The first Monday in September, Labor Day, is dedicated to the social and economic achievements of American workers, including the quantities of blood, sweat and tears they have shed in their contributions to the strength, prosperity, and Gross National Product of the United States. (As a person who once spent a summer as a card-carrying member of the United Steelworkers' Union, I can testify to the amount of sweat shed.) Depending on what you read, this holiday for workers was the brainchild of either Peter J. McGuire, a cofounder of the American Federation of Labor, or Matthew Maguire, a machinist and later the secretary of Local 344 of the International Association of Machinists. (I can see how they might be confused!) The first Labor Day holiday was celebrated on Tuesday, September 5, 1882, in New York City, sponsored by its Central Labor Union. In 1884 the first Monday in September was selected as the holiday, and the Central Labor Union urged labor organizations in other cities to follow their example and celebrate a "workingmen's holiday." The idea spread with the growth of the labor movement, and in 1885, Labor Day was celebrated in many cities with strong industrial bases across the country. On June 28, 1894, Congress passed an act making the first Monday in September of each year a legal holiday in the District of Columbia and the territories. Lately labor unions have been under attack by various factions in the U.S. political galaxy so it might be time to take a moment or two to read more about the history of labor in this country in order to fully appreciate the journey and the struggle of our predecessors. What better way to do that but with a well-written piece of nonfiction?!?  There is Power in a Union Philip Dray (Doubleday, 2010) From Lowell to Ludlow, from Haymarket Square to the ill-fated 1981 PATCO strike, the history of the labor movement has indeed been an epic journey and Dray captures it all in a crisp narrative that highlights vivid characters and dramatic scenes. Heroes, scoundrels, shining moments and scandals, the story of labor is the story of America, and it brought to life in the hands of a fine writer, who presents an even-handed account, although it is clear where his sympathies lie.  The Battle of Blair Mountain Robert Shogan (Westview Press, 2004) The violent nationwide Great Railroad Strike of 1877 may have involved more workers, but the Battle of Blair Mountain, WV, in August 1921 was the largest armed labor uprising in the United States. Nearly 10,000 white and black coal miners of the United Mine Workers of America attacked 3000 pro-coal company men. Here is a riveting tale of dissent, human rights, ancient enmities (a Hatfield of that infamous family is in the mix), and the threat of federal troops attacking citizens.  The Man Who Never Died William M. Adler (Bloomsbury, 2011) Inspiration to songwriters from Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger to Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, Joe Hill was a labor activist who became a legend. In 1915, Hill was executed in Utah for a murder it remains doubtful he committed. A proud member of the Industrial Workers of the World (colloquially known as "the Wobblies"), the most radical union of the early 20th Century, Hill was known for his humorous yet aggressive protest songs. Set to popular tunes and featured in the IWW's Little Red Songbook, they were pointed attacks on the establishment. Hill's famous "The Preacher and the Slave" mocks the hypocrisy of offering spiritual advice before worldly sustenance and introduced into the American lexicon the phrase "pie in the sky." Adler has scoured newspapers, archival sources, and related significant biographies to bring Hill's story to life and to deliver the man behind the myth. August 6th marks the 67th anniversary of the destruction of the city of Hiroshima, Japan with the first use of an atomic weapon. Thinking men and women should spend some time investigating the back story of this event and its role in shaping the world as we know it.  The Making of the Atomic Bomb Richard Rhodes (Simon & Schuster, 1986) This is the definitive work on the subject. Yes, it's long (over 800 pages) and not an easy read, but Rhodes writes in a gripping style and delivers facinating psychological insights into the personalities of the men behind the Manhattan Project. Rhodes covers it all: the theoretical origins of the bomb in the mind of Leo Szilard, the lab experiments spearheaded by Enrico Fermi and his crew of scientists at the University of Chicago, the building of the prototype, the test at Alamagordo, New Mexico, the training of the B-29 crews assigned to deliver the first two bombs and the missions themselves. He also delves into the struggle in Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan to make the first bomb, as well as the political and military events that led to the destruction of the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Well worth the time and effort.  Pandora's Keepers: nine men and the atomic bomb Brian VanDeMark (Little, Brown, 2003) VanDeMark puts his focus on the nine men who built the atomic bomb and how each struggled with the implications of their deadly creation. He does an excellent job of bringing these brilliant scientists to life in this examination of the moral ambiguity that exists in "an imperfect world that sometimes forges good from evil and evil from good." First, we witness science at work, in the act of creation that drove these talented individuals. However, then VanDeMark switches gears and tackles the issues of the aftermath, when the scientists, academics all, realized the real-world horrors and implications for the future that their creation had wrought. Pandora indeed.  Shockwave: countdown to Hiroshima Stephen Walker (Harper Collins, 2005) This high-speed rollercoaster ride of a narrative recreates a (literally) minute-by-minute retelling of the Hiroshima bombing as remembered by American soldiers, Los Alamos scientists, and Japanese survivors. He examines the doubts and fears of the bomb's designers, the thought processes behind the selection of the targets, and the bewilderment of citizens of Hiroshima, who were victims not only of the U.S. bomb, but a Japanese government controlled by men who were determined to continue the fight at all costs.  I ate up the Olympic Games when I was a child, Winter and Summer. I was glued to ABC, entranced by genial host Jim ("the thrill of victory and the agony of defeat") McKay, who also hosted "Wide World of Sports" ("spanning the globe to bring you the constant variety of sport"). I was fascinated by the foreign locales and host cities. I was thrilled by the displays of grace and strength in exotic sports of which I could only dream. In fact, I remember a writing assignment in 2nd grade in which I kept a journal, complete with illustrations, written under the persona of an Olympic downhill skier. Nevermind that I had never skied in my short life, (and still haven't) flatlander Chicagoan that I was, bred and born! I was enthralled by the dashing French skier Jean-Claude Killy and his trio of medals in the Alpine events in the 1968 Winter Olympics held at Grenoble, France. (I confess that I think I still have that relic of my childhood education tucked away in a trunk in the basement.) Of course, back in the day, both the winter and summer games were held in the same year and thus came around only once every four years, so it seemed like even more of an event. Now, with the staggered schedule, there is less of an Olympic drought in between. Perhaps that is why I am a little more blasé about them as an adult, although yes, I still watch my fill. The 2012 London Summer Olympics begin in one week, so there's still plenty of time to do a little preliminary reading and research on this mega-event which celebrates the heights of athleticism throughout the world. How about starting with a little historical perspective?  The Naked Olympics: the true story of the ancient games (Random House: 2004) Tony Perrottet A history of the original Olympic games depicts the events of the first competitions more than 2000 years ago, during which tens of thousands of sweltering-hot spectators watched nude athletes participate in such events as hoplitodromia, a full-armor sprint, and the pankration, a no-holds-barred lethal brawl. Travel writer Perrottet treats readers not only to a thorough picture of the games' proceedings but also to glimpses of the shameless bacchanalia, numerous (and often lascivious) entertainments and even corruption that accompanied them. Hmm, sounds like not a whole lot has changed...except the sporting goods companies like Nike and Reebok would never let their endorser-athletes complete sans apparel. How would they show off the swoosh? Perhaps a well-placed tattoo?  History of a more recent vintage... Igniting the Flame: America's First Olympic Team (Lyons Press, 2012) Jim Reisler The author tells the little-known story of the first modern Olympics, the 1896 Summer Olympics, highlighting the difficulties faced by a fourteen-member American team which had virtually no support heading into the games, held in Athens, Greece. Here's one remarkable anecdote among many: an American Olympian shows up for the discus event, having never really tried it before; some accommodating Greek athletes offer to demonstrate, he practice a bit and winds up winning. Reisler skillfully weaves his story from several narrative threads: the resurrection of the Olympic Games, and the men behind their revival; the primitive means of travel and lodging (no fancy Olympic Village here with 24/7 food courts); and the stories of individual athletes and events.  Hitler's Olympics: the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games (Sutton: 2006) Christopher Hilton The Berlin Olympic Games, which remain the most controversial ever held, will have their 80th anniversary in August 2016. Using newspapers, diaries and interviews to recreate the atmosphere during the XIth Olympiad, the author presents an account of the disputes, the personalities and the events which made these Games so memorable. Hitler, of course, used the Games as one of the largest propaganda exercises in history. African-American Jesse Owens won four gold medals in a shining moment for America.  A suitable companion or alternative to the above might be... Triumph: the untold story of Jesse Owens and Hitler's Olympics (Houghton Mifflin: 2007) Jeremy Schaap Schaap (an ESPN host) touches briefly on Owens's life before and after 1936, including his Alabama childhood and his later work for the State of Illinois, focusing most of the book on Owens's track and field heroics. Blessed with amazing speed, he set NCAA records in numerous events. With the help of high-school mentor Charles Riley and college coach Larry Snyder, Owens qualified for the Olympics. After a debate about whether participation in the Nazi Games was ethical—a discussion that had special meaning for African-Americans, whose circumstances were indeed similar to those faced by German Jews—the U.S. elected to compete, setting the stage for Owens to show the world a true superman not descended from Aryan stock.  Rome 1960: the Olympics that changed the world (Simon & Schuster: 2008) David Maraniss Whether you prefer sports, politics, or history, the author has you covered in this engaging study of the first commercially televised Summer Games. There were several other firsts in Rome: the first doping scandal, the first athlete paid to wear a certain brand, the first African-American to carry the U.S. flag in the opening ceremonies. The games fed Cold War propaganda as the Soviet Union surpassed the U.S. in the medal tally. Maraniss loads his narrative with human interest stories (the barefoot Ethiopian Abebe Bikila), personal rivalries, judging squabbles, come-from-behind victories and inspirational stories of obstacles overcome (American track star Wilma Rudolph). It might not be true that these Olympics changed the world, but they definitely showcased the changing world of that era. A gold medal to anyone who finishes all five before the Summer Games begin!

Henry David Thoreau, born this day in 1817, was a Renaissance man who just happened to live in 19th century America. He was a poet and philosopher who worked for a time as a down-to-earth surveyor and pencil-maker, a naturalist who reveled in the wild but was absolutely not a cranky hermit, and a tax-resister who wrote the book, literally, on civil disobediance.  "A truly good book teaches me better than to read it. I must soon lay it down, and commence living on its hint. What I began by reading, I must finish by acting." Thoreau didn't go to Walden Pond just to commune with Nature. He was looking for a quiet place to do some writing and his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson had this nice rustic place on the water. It was perfect for getting a little solitude and being able to tune-out all the hassles of modern life! I can't imagine what he would think about our wired 24-7-365 lifestyle. He might be one of those people running down the street buck-naked, his crazed rants captured on someone's iPhone and posted to YouTube as it happens. As he noted in a chapter of Walden: "I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived." He wasn't a Material Guy and frankly, wasn't pulling in a lot of benjamins at the time so he figured he could reduce his material needs by living simply, rather than support a lifestyle back in Concord that he didn't need or really care about. And if he could do a little communing and meditation, well, so much the better.  Portrait of Thoreau by Samuel Rowse (1854) In his famous lecture, "Life without Principle" given first in 1854 at Railroad Hall in Providence, Rhode Island and several more times over the course of the next year, Thoreau argued that work should be something we love in order to lead a life worth living, not simply to make a living. Well, that's all very well and good for a Harvard man to spout such idealistic notions, but he seems to have completely forgotten about the poverty-striken masses who were (and still are) struggling to pay the rent and put food on the table for their children. The ideal fulfilled life may indeed be found in pursuing a path that leads us to what we truly love to do, and then work doing that; however, the reality is that many people lack that freedom and must take a job because it comes with a paycheck. But I'm willing to forgive him because he did write a lot of great quotes about books! "Books are the carriers of civilization. Without books, history is silent, literature dumb, science crippled, thought and speculation at a standstill. I think that there is nothing, not even crime, more opposed to poetry, to philosophy, ay, to life itself than this incessant business."  Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr., Leo Tolstoy, Martin Buber and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas all have this in common: an admiration for Thoreau's essay of 1849 "Civil Disobedience," originally published as "Resistence to Civil Government." (It not clear whether he actually ever uttered the words "civil disobedience.")But beyond the big names, the essay was read in the 1940's by the Danish resistance; in the 1950's, it was brandished by those who opposed McCarthyism; in the 1960's, it was influential in the early struggle against South African apartheid; and in the 1970's it was discovered by a new generation of anti-war activists. The essay contains the famous quote often misattributed to Thomas Jefferson: "I heartily accept the motto, — ‘That government is best which governs least.'" Thoreau was actually was referring to an existing saying that was the motto for the journal The United States Magazine and Democratic Review, which was edited by American journalist and editor John Louis O’Sullivan. In 1844, Thoreau’s old pal Emerson also wrote in an essay: “The less government we have, the better.” (What's a little borrowing among friends?) Hmm, I foresee Thoreau's face soon will be glaring out at me from posters held aloft by Tea-Party protesters. Here's what his man-crush Emerson had to say about him: "He was bred to no profession; he never married; he lived alone; he never went to church; he never voted; he refused to pay a tax to the State: he ate no flesh, he drank no wine, he never knew the use of tobacco; and, though a naturalist, he used neither trap nor gun. He chose, wisely, no doubt, for himself, to be the bachelor of thought and Nature. He had no talent for wealth, and knew how to be poor without the least hint of squalor or inelegance. .... Thoreau was sincerity itself ..." You can read more about this fascinating fellow with these biographies, which range from the scholarly to the refreshingly whimsical:

Henry Thoreau: A Life of the Mind - Robert Richardson, Jr. (1988) Henry Thoreau: A Biography - Walter Harding (2011) Henry Thoreau: A Man for All Seasons - Douglas T. Miller (2001) The Thoreau You Don't Know - Robert Sullivan (2009)  I am not a "beach read" aficionado. Probably because I am constitutionally unable to do a lot of reading at the beach... or any place or time during a summer day. I am of the tribe of ants, who spend their summers toiling under the hot sun, rather than the grasshopper cohort, who fiddle from morning til night as the balmy breezes waft. When faced with a stretch of sand, whether a shell-strewn beach along the Gulf of Mexico or a pebbly shoreline on one of the Great Lakes, I am much more likely to set off on a hike to find a lightning whelk or a gnarled piece of driftwood or just exactly where that path up the dunes leads, than pull a book out of my totebag and settle in under the umbrella. However, this being the time of year when I am frequently asked to recommend "beach reads," I took some time out from spreading mulch to do a little research...  Apparently, the main requirements of a good beach book is that it (1) be engaging and (2) you can finish most of it before your sunscreen wears off, i.e., it's not likely to be "literature," but it must definitely be entertaining. So, whether you like thrillers, chick lit, or something smart but not too heavy, with these books in hand (or on your e-reader), all you need to grab is your towel and sunscreen and you're ready to read.  What Was I Thinking? 58 Bad Boyfriend Stories By Barbara Davilman and Liz Dubelman Oh, the stories women could tell. And 58 of them were willing to spill their guts in this Oprah-recommended read. They're funny and smart. But whoa, are they stooopid when it comes to knowing a relationship is dead. It can take years in breakup "Crazytown." Usually, despite countless clues, there's an epiphany: Mr. Right invites you to have dinner with his married girlfriend so you can be pals. He thinks deploying faux dog excrement at a party is hilarious. He uses "invertebrate" when he really means "inveterate" or comes home one day proudly flashing a cubic zirconia nipple ring. Try to top this heartbreaker: at the altar, he tells you he can't stand the embroidery on your wedding dress, would you mind wearing it backward? So many red flags wave in these witty, woeful tales, you'll think you're in China. A must-read for lovers of Schadenfreude.  Lots of Candles, Plenty of Cake By Anna Quindlen She's one of my favorite essayists, so, although I won't be reading this at the beach, it's definitely on my summer reading list. In this collection, she gives us rueful insights into a generation that's "still figuring things out" and still wishing to have it all, even at 60.  The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows A delightful book club read (yes, I actually have read this one) that might serve well as a beach read. It's a light piece of historical fiction set on the Isle of Guernsey after World War II that will make you chuckle, bring a tear or two to your eyes, and give you something to think about (without weighing you down with thoughts too heavy for day full of cottony cumulus clouds).  Robert Ludlum's The Bourne Imperative by Eric Van Lustbader Okay, so it's not by the original master, but if you are into thrillers, this one should serve to idle away a few hours while you are baking in the sun (and waiting for the next Bourne flick ("The Bourne Legacy") to premiere in August). Just remember the sunblock if you are prone to burns! Jason Bourne's rescue of a drowning man not only reminds him of himself (the man's an amnesiac too), it raises plenty of questions. Why is he being stalked by the Mossad? Could he really be a legendary terrorist assassin, or is this a case of mistaken identity?  Elvis, Jesus and Coca Cola by Kinky Friedman Not a deep book by any stretch, but supposedly quite entertaining. Operative word here is "quirky." Singer/songwriter Kinky Friedman's flashy mystery stars a Greenwich Village musician named--coincidentally--Kinky Friedman. When a documentary filmmaker suffers a mysterious death, Friedman's search for the missing film forces him to relive his own dark past. If you're looking for a serious book with fleshed out characters that represent the plight of human suffering, just back away from this book, grab your over-priced coffee and go find some stuffy classic. If you're looking for a quick, amusing read that offers nothing more than a cheap thrill, then pick this one up and grab yourself a margarita and a burrito-to-go. "Those who expect to reap the blessings of freedom must...undergo the fatigue of supporting it." --Thomas Paine: The American Crisis, No. 4, 1777 On this Memorial Day, I am thankful that the closest I have ever come to experiencing life in a war zone is by reading about it or listening to the oral histories of World War II and Vietnam veterans. And so a list of books, including straightforward nonfiction and memoir, that can begin to make that which is incomprehensible -- the personal experience of war -- understandable.  Dispatches From The Edge Anderson Cooper (2007) The correspondent and anchor for CNN recounts events from his life and career, offering a behind-the-scenes look at some of the most devastating modern tragedies (in Burma, Vietnam, and Somalia) and their effect on his own life.  The Unforgiving Minutes: a soldier's education Craig Mullaney (2009) From a blue-collar upbringing, Mullaney rose to graduate from West Point, became a Rhodes scholar, and then an Army Ranger. He takes an unflinching look at the ways in which his extensive military education did and did not prepare him for his experiences in Afghanistan, and how those experiences shaped his views, and his later work as a Naval Academy instructor.  Requiem: by the photographers who died in Vietnam and Indochina (1997) A photographic essay that takes readers on an emotional journey into the wars in Indochina, Cambodia, Vietnam, and Laos. Divided into five sections, the book begins with the early notions of the wars, continues through the escalation, and ends with the final days of the conflicts. Essays are included on some of the photographers, providing readers with a glimpse into the lives of these brave men and women. The photographers' accounts of the fighting provided to various news wires are also included, but the photographs are so poignant and moving that they virtually tell the stories on their own.  The Forever War Dexter Filkins (2008) The New York Times correspondent provides a firsthand account of the battle against Islamic fundamentalism, from the rise of the Taliban in the 1990s, to the terrorist attacks of 9/11, to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, offering a study of the people involved from all sides of the conflict.  Armageddon in Retrospect Kurt Vonnegut (2008) Twelve previously unpublished writings on war and peace include such pieces as an essay on the destruction of Dresden, a story about the first-meal fantasies of three soldiers, and a meditation on the impossibility of shielding children from the temptations of violence.  Generation Kill: Devil Dogs, Iceman, Captain America, and the new face of American war Evan Wright (2004) Wright rode into Iraq on March 20, 2003, with a platoon of First Reconnaissance Battalion Marines—the Marine Corps' special operations unit whose motto is "Swift, Silent, Deadly." He writes a gripping narrative on the lives of these twenty-three soldiers who led the attack, describing their training and the physical and psychological challenges they faced in skirmishes leading to the fall of Baghdad.  My Detachment Tracy Kidder (2005) Pulitzer Prize winner Kidder (The Soul of a New Machine) uses his gift for narrative nonfiction in this memoir of his year in Vietnam as a young army officer. This isn't a blood-and-guts thriller, but a story of painful self-revelation and amusing coming of age. He joined the ROTC as a confused Harvard student and ended up in a not very dangerous corner of Vietnam monitoring radio patterns. His attempts to command his detachment of bored enlisted men and his letters home, laced with fictional heroics, could have been the stuff of melodrama, but Kidder's storytelling and humor rise above. His account is an introspective, demythologizing dose of reality seen through the eyes of a perceptive, though immature, army intelligence lieutenant at a rear-area base camp. War isn't hell here; it's "an abstraction, dots on a map." |

AuthorTo find out more about me, click on the Not Your Average Jo tab. Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed